PacketFabric Column & News

Hong Kong unrest and its effect on internet speeds

This piece aims to provide you with a brief but sufficiently in-depth analysis of the political risks to companies’ internet infrastructure where it concerns Hong Kong and China, particularly the former where sometimes violent clashes have been on the news.

As a background to the clashes, in 2018 a young couple from Hong Kong flew to Taiwan for a short break, but only one came home. Mr. Chan Tong-kai had strangled his girlfriend to death after being goaded into a frenzy. Following an argument, she had shown him a porn video she shot with an ex-boyfriend. As Hong Kong does not have an extradition treaty with Taiwan (so that Mr. Chan Tong-kai can be sent to Taiwan to stand trial), a proposal was put forward to permit case-by-case extraditions to jurisdictions with which Hong Kong does not hold extradition treaties – including mainland China. Thus setting off the long-running unrest in Hong Kong as residents fear their Special Administrative Region (SAR) status becoming eroded. Mr. Chan Tong-kai is currently free.

Despite the political and legal turmoil, not to mention the well-publicized street clashes, it is actually the internet that is proving to be the critical front of this battle.

Internet Speeds Abnormal

Internet regulations on mainland China differ considerably to the laissez-faire environment in Hong Kong. Most businesses that “sell” or more specifically “provide content” to mainland China locate their IT infrastructure in Hong Kong. The rationale for this arbitrage lies in the requirement that content providers in mainland China must apply for an “Internet Content Provider” (ICP) license. Getting a license requires firms to jump through hoops and wait at least two weeks. Sometimes they are rejected. Furthermore, ICP licenses aren’t granted to foreign companies – requiring some form of joint venture or partnership with a local Chinese firm. That’s a whole other process requiring hard-nosed negotiations and lawyers on both sides (and costs!).

What is interesting is that native Chinese companies also choose to locate their IT infrastructure in Hong Kong. We speculate that this is due to the changing nature of the internet, where platform companies are not really “content providers” per se, but the “processors” of content without much control over what users post (think Facebook). In a country which regularly and openly censors content, “processors” loathe to be responsible/accountable for their users’ actions. So it is simply easier to base IT infrastructure outside of mainland China and that destination has traditionally been Hong Kong.

While the legal environment in Hong Kong has not changed since the unrest began, unofficially it appears though that internet speeds are being affected significantly. Below is a table which shows the difference in connection speeds to two mainland Chinese universities from Hong Kong and Tokyo.

——————————————————————————————————

Access point: INAP Hong KongーPeking University 331.0ms

Access point: INAP TokyoーPeking University 61.3ms

——————————————————————————————————

Access point: INAP Hong KongーShanghai University 399.5ms

Access point: INAP TokyoーShanghai University 38.6ms

——————————————————————————————————

INAP has a POP located in Hong Kong. Ping tests performed in October 2019 showed a marked latency increase.

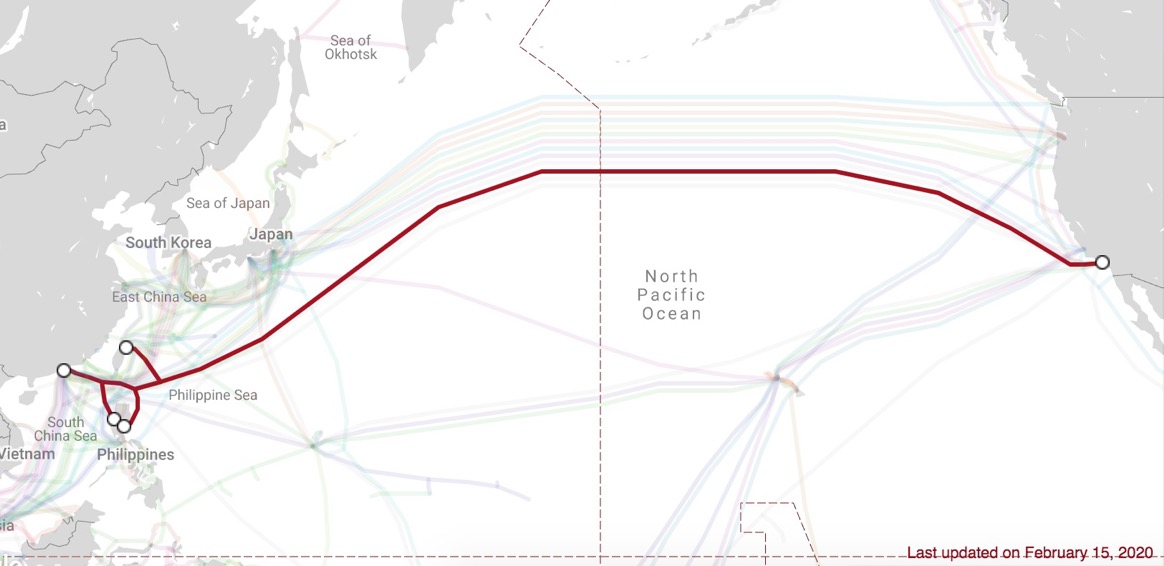

While it is not possible or appropriate to speculate on what may be its cause, the speeds are certainly unnatural. Landing points in Hong Kong and Japan are about as far from Shanghai as each other as this map of submarine cables shows:

(Asia Pacific Gateway submarine cable. Map data: Google)

The question is then, what might be the cause of this latency difference?

This is purely speculative, but for example it could be that China Unicom devices are being reconfigured, or that traffic originating from Hong Kong is being intercepted (for monitoring or censoring, for example). Either theory could explain the latency difference, but we have no proof, only theories.

However, if we are to accept that the internet is the battleground of the 21st century on which nations will assert its geopolitical will, then it’s also useful to look at what happened with Google and Facebook’s jointly owned submarine cable in 2017/18.

Google and Facebook Left Standing

In 2017, the two US tech giants, along with a third investor called PLDN, announced plans to invest in a 120 terabit-per-second undersea cable called the “Pacific Light Cable Network” (PLCN), connecting the US mainland with datacenters in Asia. This third investor, PLDN, was led by a Chinese businessman who then transferred a percentage of ownership to a fourth party, mysteriously named “Dr. Peng Telecom & Media Group” which is said to hold a strategic partnership agreement with Huawei. This set off a legal intervention with US regulators which forbade data to flow through the cable, pending review. Then, in light of the unrest in Hong Kong, US Senator Rick Scott sent a public letter to Ajit Pai, Chairman of the FCC, urging the FCC to block PLCN because it “threatens the freedom of Hong Kong”. (Source: https://licensing.fcc.gov/myibfs/download.do?attachment_key=1977983).

Google and Facebook have since sought to manage their losses on the PLCN cable (which is now only partially operational), by respectively starting operations of their own sections of the cable to Taiwan and Philippines but notably not to either mainland China or Hong Kong.

(Pacific Light Cable Network submarine cable. Map data: Google)

While the PLCN network remains in limbo, cables routed through other countries (and jurisdictions) will pick up the excess data flow.

Performance will not be as high as with the full PLCN in operation, however.

Learning Points

The main takeaway from this series of developments is that political risk in IT infrastructure has never been higher.

Companies with online presence in China would do well to evaluate their position and consider more politically “neutral” locations for their servers.

Any latency above 200ms is quite unacceptable to online gaming, gambling, cloud computing and financial intermediaries.

INAP Japan has witnessed a surge in interest from Chinese companies deeming Tokyo to be a “safer” location for their servers compared with Hong Kong. Japan is politically stable, with high quality infrastructure (high availability, redundancy and capacity) making it an attractive base. INAP Japan has multiple points-of-presence in Tokyo and in Osaka.

As the turmoil in Hong Kong shows no sign of abating, and with precedent set, it appears that businesses will need to reevaluate their infrastructure decisions and consider alternatives to Hong Kong to locate their infrastructure.

Unfortunately, Hong Kong is not the best place right now in the era of the internet. Of course, we hope that INAP Japan can benefit, but at the same time wish for peace on the streets of Hong Kong.

Julian Israel

Marketing Strategist, INAP Japan

- Call us

- +81-3-5209-2222